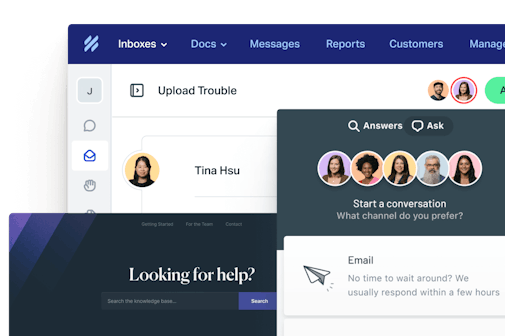

Here’s a situation you can probably relate to: you A/B test a landing page on your website to see which one resonates most with customers.

The result shows that B is clearly better than A, but your heart and intuition are stuck on the former. You look at the data and all the red arrows pointing down, yet you feel as though something is off. You find opinions and research that confirm that even though B is better, A is still an okay choice and it won’t kill your business.

This is the working of a cognitive bias.

Our minds naturally categorize things based on our past experiences and memories—good or bad. These biases helped our ancient ancestors survive, and they’re still useful today when meeting a stranger or walking home at night. In short, these biases are like mental shortcuts that help us to quickly navigate through a multitude of decisions. However, they don’t always lead us to the best, most intentional decisions—especially in the workplace.

Here are four types of cognitive bias that can sabotage your workplace if left unchecked.

1. Unconscious bias

Hidden or unconscious biases are bits of knowledge that are stored in your brain. They are formed by the culture that surrounds you—media, propaganda, group-think, stories, jokes, and language. They influence how you think and behave toward a particular group of people.

The scary part? You (and all of us) can be oblivious to their power. A perfect example comes from psychologists Mahzarin R. Banaji and Anthony G. Greenwald in Blindspot: Hidden Biases of Good People:

“A father and his son are in a car accident. The father dies at the scene and the son, badly injured, is rushed to the hospital. In the operating room, the surgeon looks at the boy and says, ‘I can’t operate on this boy. He is my son.’ How can this be? (Continue reading when you either have an answer or conclude that you have none.) If your immediate reaction is puzzlement, that’s because automatic mental associations caused you to think ‘male’ on reading ‘surgeon.’ The association surgeon = male is part of a stereotype. In this riddle, that stereotype works as the first piece of a mindbug. The second piece is an error in judgment—in this case a failure to delay in figuring out that the surgeon must be the boy’s mother.”

It’s surprising how unknowingly biased we can be, even with the best intentions at heart. Of course women are surgeons, but the example above shows how culture has led our minds to believe and automatically process that surgeon = male.

This example barely scratches the surface of all the possible biases in the workplace. From hiring, onboarding, and building relationships, these unconscious biases lurk in the corners of our minds.

Mindfulness shines a light into these corners, allowing us to have empathy for differences and to avoid misusing language that may not seem harmful but is very meaningful for the other person’s sense of belonging.

2. Confirmation bias

As described in the example above, this type of bias happens when we seek information that confirms our opinion or worldview while avoiding or deflecting information that threatens it.

People who believe that vaccines are dangerous don’t usually search for information that shows they’re wrong—and if they do, it turns out, they remain evermore resilient in their beliefs. Being wrong or seen as a fraud is innately painful—it goes against the desires of human nature and social connection.

It’s far easier to apply the balm of self-justification than it is to show your scars.

The solution, then, is to be open-minded. Let’s say you meet a new co-worker and, because this person is nervous, he or she tells an inappropriate joke. You take it well and laugh it off, but you feel annoyed. Now you’re off to a bad start, and this first impression has colored your perception about the person. It can be difficult to disregard the experience and start over, as our minds still want to use that experience as an anchor and compare it to future experiences.

Learn more about confirmation bias in this video from Big Think.

3. Self-serving bias

Perhaps one of the most amusing but fundamentally important examples is the self-serving bias, meaning we have a tendency to look at ourselves through rose-colored glasses and accept our successes more highly than our failures.

Social psychologist David G. Myers says the following in his book, This Will Make You Smarter:

“In experiments, people readily accept credit when told they have succeeded, attributing it to their ability and effort. Yet they attribute failure to such external factors as bad luck or the problem’s ‘impossibility.’ When we win at Scrabble, it’s because of our verbal dexterity. When we lose, it’s because ‘I was stuck with a Q but no U.’ [...] Studies of self-serving bias and its cousins — illusory optimism, self-justification, and in-group bias — reminds us of what literature and religion have taught: Pride often goes before a fall. Perceiving ourselves and our group favorably protects us against depression, buffers stress, and sustains our hopes. But it does so at the cost of martial discord, bargaining impasses, condescending prejudice, national hubris, and war. Being mindful of self-serving bias beckons us not to false modesty but a humility that affirms our genuine talents and virtues and likewise those of others.”

To overcome this, it’s important to gather feedback from a diverse pool of perspectives. It opens up a wide range of ideas and thoughts instead of having tunnel vision for the dominant belief.

Above all, we need to overcome our selves, starting with our egos and emotional attachment to a particular outcome or idea.

4. Negativity bias

Like getting one C among all As on a report card, our eyes become glued to the bad grade. The same happens in business; a company may have had one of its most successful years, but there are still meetings created around the one failure it experienced.

This isn’t because we’re pessimists or overly ambitious; it’s because we’re human.

The social psychologist Jonathan Haidt, in Happiness Hypothesis, explains why we have a preference for the bad over the good:

“This principle, called ‘negativity bias,’ shows up all over psychology. In martial interactions, it takes at least five good or constructive actions to make up for the damage done by one critical descriptive act. In financial transactions and gambles, the pleasure of gaining a certain amount of money is smaller than the pain of losing the same amount. In evaluating a person’s character, people estimate that it would take twenty-five acts of life-saving heroism to make up for one act of murder. When preparing a meal, food is easily contaminated (by a single cockroach antenna), but difficult to purify. Over and over again, psychologists find that the human mind reacts to bad things more quickly, strongly, and persistently than to equivalent good things. We can’t just will ourselves to see everything as good because our minds are wired to find and react to threats, violations, and setbacks. As Ben Franklin said, ‘We are not so sensible of the greatest Health as of the least Sickness.’”

Celebrate your wins, learn from bad experiences, and always remember one is not inherently better or worse than the other, but our thinking makes it so.

We can overcome the default settings of our biases by practicing mindfulness, acknowledging the underlying trickster, reflecting on our behavior, and being intentional in our decision-making.

Be aware of biases specifically in times of great importance, such as hiring and onboarding, and seek to develop methods that engage objectivity. We will never be able to totally banish biases from our minds, but we can learn to understand them and the way they influence how we lead our lives.