When we started Help Scout, I don’t remember any of us making a conscious decision to build a fully remote company. It was more of a survival strategy.

One of my co-founders needed to work from Nashville for the first year or so. Then, some of the most important early hires we made wouldn’t have joined our team unless they could work remotely. From the beginning, we needed the capacity to work together without being in the same location.

Since then, we’ve become very intentional about building a remote team. We spend a lot of time and money investing in the culture and making sure people across 80+ cities around the world are empowered to do great work. Through trial and error, we’ve learned a lot along the way.

This guide is a compilation of some of the most important remote management lessons — from how to hire employees to how to build a thriving company culture — that I’ve learned running a fully remote company for the last nine-plus years.

Prefer to watch a video instead? Check out this webinar on taking your team remote, featuring Help Scout's CEO Nick Francis and People Ops Partner Morgan Smith-Lenyard.

How to hire remote employees

When Jared, Denny, and I founded Help Scout, none of us had ever hired anyone — ever — and it showed. Not only did we have a lot to learn about hiring, but we also took too long to recognize a misalignment and part ways with people.

From 2011 through 2014, we hired 17 people at Help Scout. Eleven of them (65%) were eventually let go. Of the people we let go, their average tenure was 19 months.

From 2015 through April 2018, we hired 75 people, and only 13 (17%) of them were let go. For 2016 through 2019, the average tenure of people who were let go was about 4 months.

I take 100% responsibility for every hiring mistake, but it’s still no reason to keep someone on the team who could be doing better work elsewhere.

As a result of our early hiring mistakes, we’ve put countless hours into refining the hiring process. Not surprisingly, as we got more thoughtful and structured, we made fewer mistakes.

Here are a few strategic adjustments that have made an impact.

Do a project

Because of our relative inexperience hiring people early on, we learned not to put much weight into our interviewing skills. Instead, we asked people to show us what they could do with a project. Right away, working with candidates on projects improved our hiring success rate.

Obviously the project is dependent on the role, but we structure them similarly:

We ask the person to spend 6-8 hours of time on it — no more. Since they have a day job and home life, there’s no deadline.

As an acknowledgement of their time and effort, we ask them to invoice us at a rate of $30/hr. It’s not much, but it’s a nice way to show people that we value their time.

We set up a Slack room or email thread for questions and collaboration on the project. This is an important part of it for us — we want both sides to get a feel for what it’s like to work together, and written, async communication makes up the bulk of it.

We have 1-2 people on the team, who aren’t involved in the hiring process, review the project with fresh eyes. They shouldn’t know anything about the candidate going in. This helps eliminate unconscious bias in the hiring process.

We’re big fans of asking for a post-mortem, which is a one-page or so self-reflection on the project, where we ask questions like: How did it go? What did you learn? What would you have done differently? What would you do next if you had more time? What would have made the project better? We learn a lot about people by reading their own evaluation of their work.

We offer constructive feedback to make sure the candidate walks away with something helpful in exchange for their time. Even if we don’t end up hiring them, we want them to have a good experience with the company.

Sometimes the project is doing the work (writing or designing something), but other times we might ask the person to create a presentation. We’ve asked managers, for instance, to put together a presentation of their Manager ReadMe, or for Growth Marketers to evaluate our paid marketing efforts and make some suggestions.

There are a few keys to getting the project right:

Be creative!

Make sure the work would be part of their day-to-day role

Design it so that good work can be done in the time allotted

Try to avoid requiring the candidate to know/obtain any business or product-specific context

Ask for candidate feedback at the end so you can improve the project

Without a project, your hiring process will implicitly give preference to good interviewers. Ultimately it’s about the work, and it’s important to come up with a process that takes that into account. It’s one thing to take someone’s word for it, and another to actually work with them and see how it feels.

Seek people who are in love with the work

The two things I look for when hiring for our remote team are:

A track record of excellence

A love for the craft

We’re looking for people who know exactly what they want from their career and who just need a culture that will give them enough ownership to do their best work.

While I’d like to think of Help Scout as a collaborative environment, a lot of people on the team spend 4-6 hours heads-down every day, working on hard problems. We need folks who can make the most of that time and require little to no direction to do great work.

Hiring aspirational candidates — people fresh out of school or doing this type of work for the first time — doesn’t work well on remote teams. As much as we’d like to hire more junior folks and see them fulfill their potential, it’s much more challenging in a remote culture for both sides.

Several of our early hiring mistakes had to do with hiring aspirational folks who were great people, but who weren’t going to do their best work at Help Scout.

By hiring experienced candidates, we’ve realized the benefits of surrounding everyone with high performers who continue raising the bar.

Optimize for work-life harmony

Remote work skeptics often assume people work less when they aren’t going into an office. My experience has been quite the opposite.

When you hire people who love the work, they might end up doing it for 12-14 hours a day before they even realize it. Obviously, this isn’t sustainable or healthy, which is why we look for a high level of self-discipline and work-life harmony when hiring people.

Remote workers need things pulling them away from work, like family, hobbies, and other passions. When people are disciplined about maintaining work-life harmony, three great things happen: They don’t burn out, they do their best work, and they’re happy working at your company.

Make remote part of your brand

In 2019, 8,403 people applied for roles at Help Scout. Of that group, we hired 41, which is a 0.48% acceptance rate. For comparison, Harvard accepts 6% of applicants, and Google hires 0.2% of applicants.

It’s also worth noting that we only post our jobs on one or two highly targeted job boards (if any). We never use the larger sites where you can easily get hundreds of unqualified applicants. The quality is quite high for the roles we post.

I say this not to brag but to demonstrate the importance of making remote work synonymous with your brand. Remote work is clearly part of Help Scout’s DNA — something we’re passionate about — and it’s obvious to people considering a role with us. It took us several years of investment to see this level of quality in our hiring pipeline.

Experienced remote people are well aware that the “remote-first” philosophy must be adopted in order for them to be successful. If they don’t see that in your company, they likely won’t take the risk.

Our goal is that when a super-talented person wants to work remotely, Help Scout is in their top five. No doubt we have stiff competition with great companies like Zapier, Automattic, Buffer, and Basecamp, but we invest significant time and resources into remote culture to be among those top choices.

Change the hiring process

When I lived in Boston, I noticed that a talented person would be on the market for a matter of days before being scooped up. It’s incredibly competitive, and in my experience, it’s easy to make mistakes when hiring this quickly.

Hiring remotely is different. On average it takes us about 40 days to fill a role and roughly three weeks for a candidate to go through the full process. Every role includes a project, as mentioned above, and we like to go back and forth, giving folks critical feedback and simulating what it will be like to work together.

A thorough hiring process is also a wonderful candidate experience. It gives both sides a lot of time to carefully consider whether this is a perfect fit, and it gives the candidate the chance to get to know several people on the team. When the process is more thorough and involves more people, it’s also easier to steer clear of unconscious bias.

I can only remember one time in seven years that we lost out on someone for not moving fast enough. That’s a risk we’re willing to take in favor of making the right decision.

Recruit to diversify the hiring pool

The data is abundantly clear: Diverse companies are more successful. At Help Scout, we do proactive recruiting to add more balance to the hiring pool. Without proactive efforts to make the applicant pool a reflection of the general population, it’s almost impossible to build a team with varied opinions, perspectives, and experiences.

Unfortunately this wasn’t always a focus for us, and we had significant “diversity debt” to account for when this became a priority in 2016. But I can say that changing the candidate mix in our hiring pool has transformed our team in unbelievably positive ways.

As a remote team, by way of having a larger talent pool, your opportunity to hire people from underrepresented groups is far greater.

It’s important to make the most of that opportunity and to hire a recruiter to source diverse candidates as soon as you can.

How to structure a remote team

It’s harder to be a manager in a remote culture. It’s a lot more time-consuming to keep up with all the information streams: Someone is always working, even when you sleep. In a co-located company you may have a morning stand-up meeting for 15 minutes. At Help Scout, stand-ups are written updates in Slack, and they appear at all hours of the day.

One way we’ve worked to resolve this problem is to organize our team into dedicated “players” (individual contributors) and “coaches” (managers). These words reinforce important associations for us culturally. When you think of professional sports, players come first. Fans wear player jerseys for a reason.

Players (designers, engineers, writers) are the heart and soul of Help Scout. They embody what we want to be about. A coach’s role is to serve players, to help them seek excellence, and to ensure their team is greater than the sum of its parts. This speaks to the servant leadership we want from our coaches. There’s no room for “command and control” leaders in our company.

Players play; coaches coach

On a small team, even within a larger company, it’s often necessary for people to take on the role of a player-coach. Being a player-coach isn’t a bad thing, but we’ve found it’s usually suboptimal; context-switching between roles can be deeply distracting.

Once a team reaches six to eight people, we try to have any player-coaches choose the path they are most excited about, then hire for the role they leave. They don’t have to take a salary cut, and now they’re able to focus on a single role to be at their best.

Keeping these roles as separate as possible helps reduce excessive hierarchy. When coaches are in a dedicated role, they can serve anywhere from eight to 12 people. With a hybrid consortium of coaches and player-coaches, you could end up having six people with direct reports on a 22-person team, which is a telltale sign of superfluous management overhead.

While there will always be exceptions, we always try to stick with the distinction that “players play; coaches coach.”

Two types of leadership

In every company, there are two distinct types of leadership: People leadership and domain leadership.

Career ladders should reward leadership, but that shouldn’t be defined as how many direct reports someone has. If a designer on your team contributes to open source projects, writes and/or speaks regularly, and most importantly, raises the quality of work done by the entire team, they’re exemplifying domain leadership.

The last thing we’d want to do is force the designer to become a manager, because they clearly have valuable skills as a maker.

When players lead, they should be able to climb the career ladder just like anyone else. Requiring great players to manage people in order to make career progress puts both groups on the road to dysfunction because those players will likely end up in less valuable roles.

I learned this lesson the hard way with Denny Swindle, our CTO and one of my Co-founders at Help Scout. As our company grew early on, we did the natural thing and put Denny in charge of all the engineers we hired. Before we knew it, he was a coach.

Denny would tell you he wasn’t at his best as a coach. When he had to spend the bulk of his time managing projects and people, he wasn’t able to be the technical architect we all depend on, which created tension in our relationship.

Thanks to some help from an outside advisor, we quickly realized that Denny’s passions and skills were most aligned with being a player. Leading people wasn’t the best or most desirable use of his time, but as a domain leader, he remains critical to our business.

Today, Help Scout’s VP of Engineering is Megan Chinburg, and she complements Denny in every way and frees him up to be at his best as a player.

Finding alignment on compensation

The player/coach system works best when everyone is climbing the same career and compensation ladder. At Help Scout, our ladder takes the form of a salary formula. While individual salaries remain private, the formula and all the numbers are transparent within the company.

Players and coaches are measured on the same scale, which considers three factors:

Experience: A combination of excellence in your craft, your velocity, and your ability to contribute new ideas and best practices.

Impact: Your effect on everyday team productivity, on your peers, and on the business as a whole.

Leadership: Your level of independence, influence, and how you use your skills to change the course of both your team and the business at large.

I’ve seen players and coaches demonstrate these things at high levels. It may look different, but the business value created is the same, therefore the compensation and career path should look the same as well.

We check in on career goals every six months. There are times when a player expresses desire to become a coach someday, and we want to give our support. However, since we try to have a player/coach ratio of about 7:1, there are also times when that opportunity lies outside of Help Scout. That’s okay, too, and we’d prefer to have that sort of discussion out in the open.

You have to give players a path

Everyone at your company depends on significant opportunities for career progress. Without career growth, you can’t expect to keep talented people in any role.

In some companies, the greatest players are given no choice but to set their sights on some VP-level job where they have to abandon the work they love in order to manage people. I’m advocating for another path that gives them the same sense of purpose and career progress but also aligns with their skills and passions.

It doesn’t form naturally, so as a leader, you must create that path for them.

How to build culture in a remote team

There are a number of reasons why I’m passionate about remote work, but the most important reason is talent. What’s most exciting to me in life is working with people who are a lot better than me and who force me to learn at a high rate. I can’t get enough of it, which is why I’m so fiercely committed to this way of working.

Like a lot of other small businesses, Help Scout is in a market surrounded by companies with more influence, more people, and much greater resources. The only way we can win is to use constraints as an advantage, to invest in things we can’t write a check for, and to build a team of people who can punch way above their weight.

Doing remote well gives us a considerable advantage that we can’t just buy: We have access to people most companies don’t.

But access to a broader talent pool has to be earned. You have to build a company people want to work for and a culture people want to be part of.

It’s been a journey, but our most recent employee engagement survey had our highest engagement scores to date, with an overall engagement score of 91% (via CultureAmp). And when filtered by demographics, engagement was even higher among women at 93%.

Identifying and embracing the key principles below, along with a lot of hard work, enabled us to get to this point.

Go all-in on remote, or don’t bother

If you want remote company culture to be all or part of your culture mix, you have to be “remote first.” It’s hard for companies to change once they’ve chosen a way of working, which is why remote culture has to be an inalterable part of your company’s DNA.

A culture’s effectiveness revolves around how information flows. Everyone needs to feel like they have access to the same information, but remote and co-located cultures share information differently.

For example, let’s take the common trap a lot of co-located cultures are falling into today, where they make exceptions for certain people to work remotely so they can dip their toe into the talent pool. This is a recipe for disaster because the company hasn’t changed the way they share information.

Once someone goes remote, they miss out on information in impromptu meetings, on whiteboards, at the proverbial water cooler, and when grabbing drinks after work. Very quickly, they’ll feel out of the loop and unhappy, unable to do their best work.

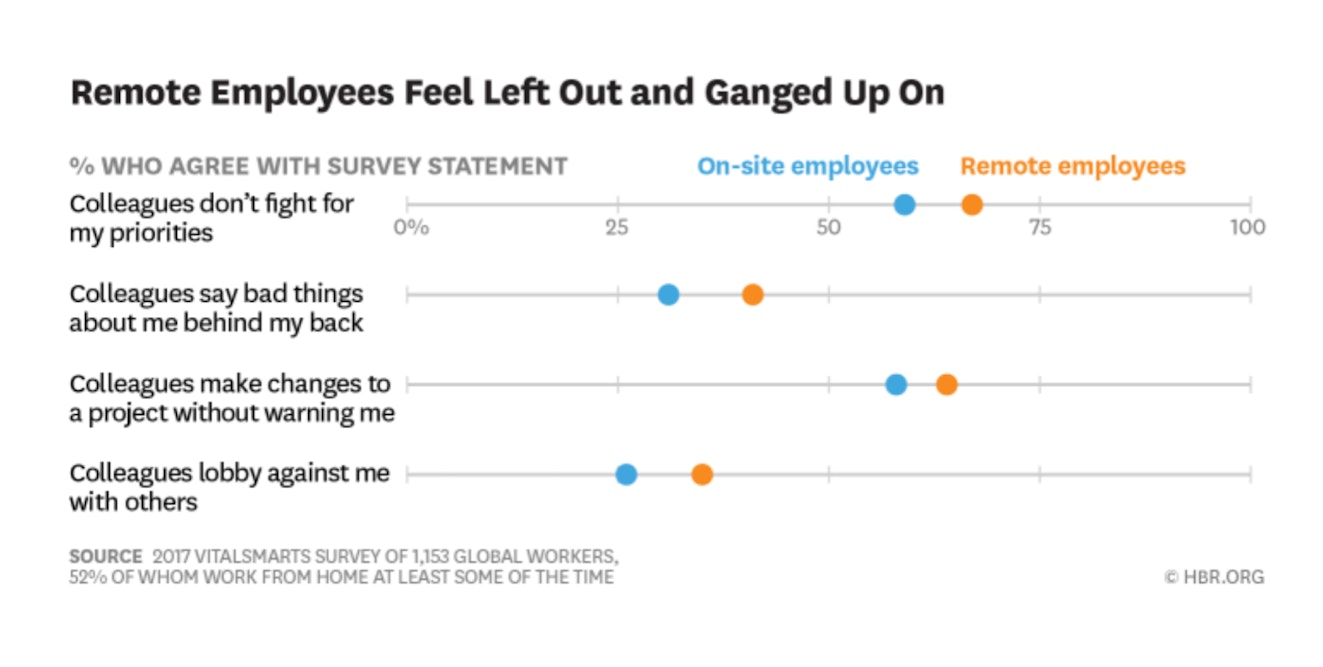

This study of 1,100 remote employees makes the point painfully clear:

When a company doesn’t change the way it communicates when the first person goes remote, it will fail to realize the benefits and likely alienate those people.

At Help Scout we have two offices — one in Boston and one in Boulder. Neither has a kegerator, a ping pong table, a whiteboard, or office perks. Every room is wired for one-click video calls with teammates, and you’ll find the ambiance to be more like a library than an office.

We do this intentionally so that even in an office, it’s the same environment our remote colleagues have with the same benefits.

Invest in People Ops

One of the smartest things we’ve done as a company is invest in People Ops. Compared to co-located cultures, we’ve always needed a disproportionate number of people focused 100% on the team and the culture. We had a three-person People Ops group at 25 people, and today (at 109 people), we have five people on the team.

A lot of the issues faced by co-located companies at 50, 75, and 100 people actually have to be addressed in a remote culture at 10, 20, and 35. For Help Scout, those smaller numbers were much more challenging than growing to 50 and 75 people.

Our retention and engagement numbers show the ROI of our investment in the culture over the years. In our history, we’ve hired 173 people, and only 20 (11%) have left voluntarily. (Six of those 20 were already on a performance plan of some sort and were likely going to need a different fit anyway.)

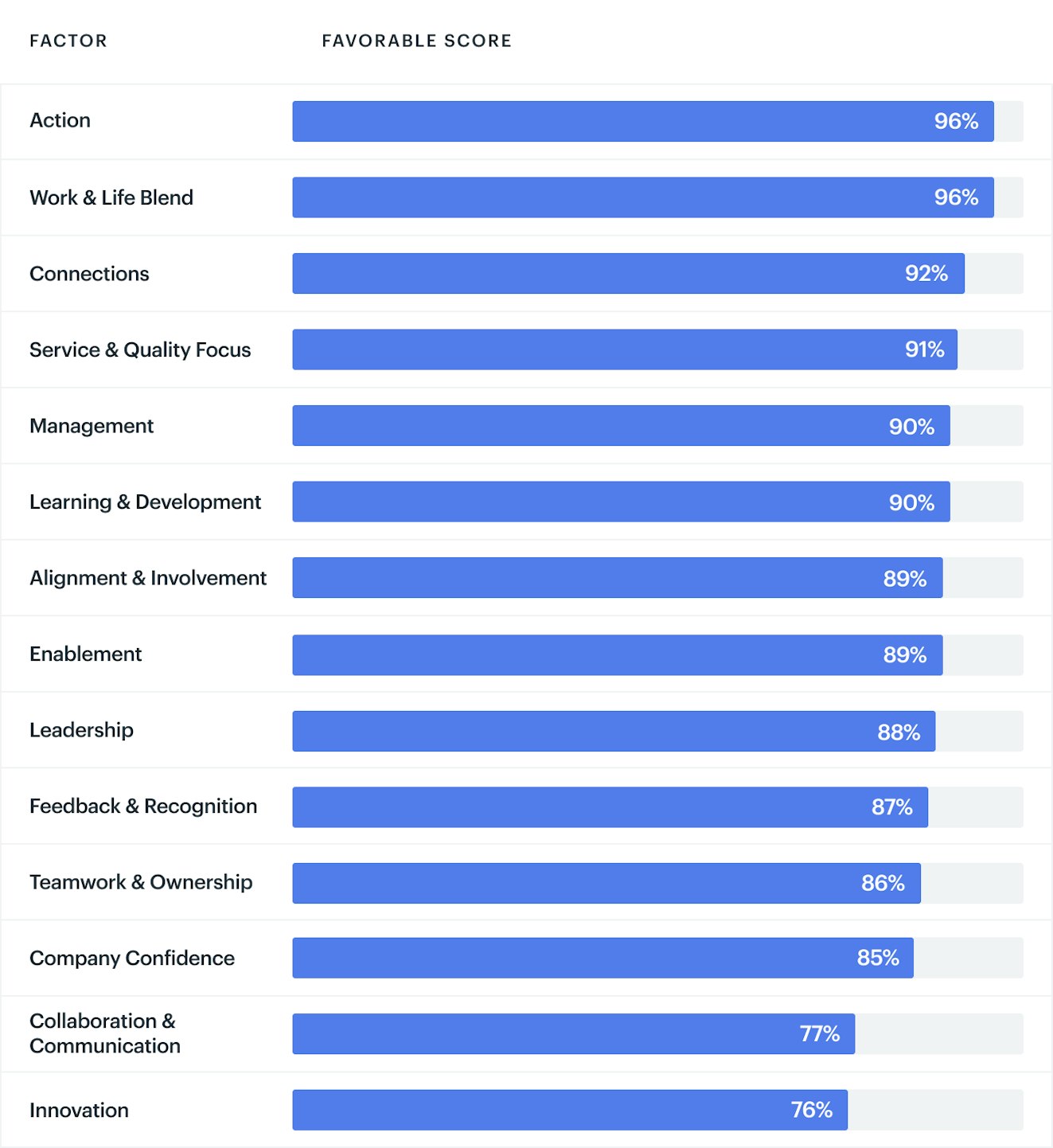

While we are working to improve areas such as innovation, collaboration and communication, and company confidence, our other employee engagement numbers speak for themselves:

Of course, none of these exist in a vacuum. When we make a few improvements, we see scores go up across a few categories.

Focus on building relationships

In a remote culture, it’s easier to get a productive 4-6 hour block of work done during the day. But one of the tradeoffs you make is that it’s not natural to develop close relationships with your teammates. Aside from work-related discussion, there are no social outings, no casual lunch conversations, and usually no friendships that also exist outside of the workplace.

Whereas relationships come naturally in a co-located culture, you have to work at it remotely. We spend a bunch of time on relationship-building, hosting semi-annual company retreats and quarterly leadership off-sites, and we hold all meetings on Zoom, our preferred video conferencing tool.

Managers also have to work hard to build and maintain great relationships with their teams. It’s a lot harder being a manager in a remote culture than it is in a co-located one.

Communication tips for remote leaders

Asynchronous communication is, obviously, a huge part of leading a remote team. Most of your communication will be written — information needs to be written or recorded so that it’s easy for people to consume on their own time. You’ll also have to adopt a level of transparency that feels uncomfortable at first so that everyone feels connected to the business.

But after asyncing everything at Help Scout, I looked around one day and wasn’t happy with the monster I’d helped create. Miscommunications happened often, projects moved too slowly, and I was too quick to get angry or frustrated. I didn’t know it was possible, but our team, which was around 75 folks at that time, had become too async to do our best work.

I ended up making a small adjustment in roughly 20% of my interactions at work. Instead of communicating async about 90% of the time, my goal was to dial it back to 70% and see how it felt. Instead of a Slack chat, I’d suggest a Zoom video call. When a spec or post was finished, I’d insist on a video chat to sync and make sure everyone was aligned.

After four months, I observed a huge improvement. Sure, it meant more meetings, but miscommunications happened less frequently, projects got stuck less often, and I was less likely to get frustrated.

Below are a few scenarios in which I’ve found the most value by connecting face-to-face.

Delivering critical feedback

I’ve always defaulted to having difficult conversations face-to-face, but it’s helpful to extend this to almost any form of critical feedback. Instead of leaving critical feedback in a comment or another async channel, I’ve started to write it down (but not send it), then schedule a video chat with the person (or people) involved to talk through it.

There are a couple of benefits to this approach. First is getting across all the non-verbal cues (facial expression, tone of voice, etc.) that aren’t available to you in a comment thread. I tend to come across as harsh with feedback unless I’m able to communicate the non-verbal cues as well.

The second benefit is the fluid conversation and additional context both sides can share in real time. I'm less likely to dig my heels in and more likely to change my mind when I'm talking through something face-to-face.

Whereas a comment thread can go on for days and end up getting contentious in some cases, a face-to-face chat can move a project forward and strengthen a relationship in the span of 10 minutes.

Pairing on challenging problems

At our last company retreat, I witnessed what must be rather commonplace in co-located companies: I saw four engineers huddle for an afternoon and solve a problem that we’d been spinning our wheels on for weeks. In a matter of hours, sitting around a table, they solved it.

Since then, I’ve asked other teams to pair up on problems more often. Pairing is common on engineering teams, but even outside of engineering, I’ve been encouraging folks to pair on problems or ideas together.

I’ll be the first to admit that pairing flies in the face of what makes me comfortable socially, but the more I’ve practiced it, the more comfortable I’ve become. And I’ve experienced several moments like the retreat where a hard problem was solved or a project moved forward that otherwise may have taken weeks.

Project kick-offs and sync-ups

This one sounds silly in retrospect, but we’d become so async as a company that we’d start and execute on large projects without gathering everyone in the room to review the plan.

Because our projects lacked a true kick-off with all of the participants, we’d experience miscommunications throughout. These miscommunications would continue because the team had no regular cadence of reviewing progress and changes along the way.

The fix was easy. Every time we start work on a project, there’s a kick-off meeting including all of the participants. On projects that include more than a few people, we also conduct a weekly sync meeting for everyone. Maybe it only lasts 10 minutes, but it keeps everyone rowing in the same direction.

Changing the venue for long chats

One other trigger I’ve been working on is any conversation that starts to draw out or get into debate territory. Maybe it’s a chat that escalates, or maybe you spend more than 10 minutes drafting an email or comment.

It’s not the answer in every case, but when in doubt, I’ve learned to stop myself and ask to chat with the person face-to-face instead of continuing things asynchronously.

This technique is especially effective (yet hard to do) when conversations get tense. In a remote company, it’s even more critical that they are dealt with face-to-face so there are no lingering ill-effects. Imposter syndrome is common on remote teams, and leaders have to be especially sensitive to what their teammates are thinking and feeling.

Find your own balance

I still love how wonderful it is to communicate asynchronously on a remote team. But we should be honest with ourselves — by default, co-located teams do the face-to-face thing much better. A more synchronous approach is instructive and a heck of a lot more efficient in a number of cases.

In my experience, a 70/30 async-to-sync ratio is a bit more healthy than something like 90/10, but it’s not an exact science. The important thing is that changing my approach has made a positive impact on our team, and it’s enabled me to strengthen relationships with several people.

Parting ways with a remote team member

I remember being terrified when I had to let a Help Scout team member go for the first time, especially since an in-person conversation wasn’t an option. Sadly, I’ve made my fair share of hiring mistakes since then and had to let more people go, but the silver lining is that I’ve learned a lot along the way about how to make the best of a tough situation.

Of course, firing someone isn’t anywhere near as unpleasant an experience as being fired. For the person being let go, it’s a scary, life-altering moment.

For that reason, it’s crucial to remove all the pain and uncertainty you can from the process. Put yourself on the other side of the table, and make it about them. The decision has been made; now it’s your job to deliver the news with sensitivity and compassion. Here’s how to do just that.

Use video

When you can’t be across the table from the team member you’re letting go, video is the next best option. The person needs to see your face, read your body language, and understand that you care deeply for them and are sincere in helping them move on in a positive way.

I fired someone over the phone once, and I will never do it again. It was awful; I felt like a total jerk. The person started crying, and I wasn’t prepared for what a cold experience it was for them. It’s been several years and I still feel terrible about it.

Don’t wait

The conventional wisdom is to wait until Friday to fire someone, but I couldn’t disagree more. It’s pointless and cruel to hang on to a team member after you’ve already decided to part ways with them. Imagine what a crummy feeling it is to know you just worked an entire day for the company that fired you. It should happen the morning after you decide.

When you hold the conversation first thing in the morning, it gives the person the whole day to let it sink in, take a walk, whatever they need to do. It also gives them time to consider how they will share the news with people close to them.

And don’t schedule anything in advance — ask the person to chat right away so they don’t see a meeting with you on their calendar and fret all night about what that might mean.

Have someone else in the room

The conversation could be difficult for a number of reasons — both for the manager and the person getting fired — so it’s useful to have an advocate from People Ops/HR there who can buffer any difficult conversations, explain benefits, and keep the conversation focused on next steps.

In most cases, it’s not necessary, but occasionally what’s said during this type of meeting can become the subject of a lawsuit. For this reason, it’s also a best practice to have a witness present to observe what happens and hear what gets said.

Get to the point

Don’t beat around the bush or try to make small talk at the outset. It should be clear what’s happening after the very first sentence.

The separation details (e.g., today is your last day, here’s what the severance package looks like, we’ll do everything we can to support you in the transition, etc.) should only take a minute to explain — try to cover everything before giving them a chance to speak.

Go over next steps and walk them through what happens next. Outline what’s required before you can pay any severance. This varies based on the situation, but usually it includes returning (or purchasing) company property and signing a termination agreement. It’s also a good idea to give a confidentiality reminder.

Make it clear you’ve been thoughtful about setting them up to land on their feet. Ask if they have any questions when you are finished explaining your part, and then…

Stick around to answer questions

At this point, the person might have questions about why this is happening. Only get into the reasons if they ask. If you do it right, they’ll know the decision has been made and there’s no going back, so it’s pointless to discuss the why — it’s best to talk about logistics and what’s next.

This time is for them, so make it clear you’ll hang around to answer any of their questions and make sure the details are clear. Give yourself a few hours before you have another commitment. Stay as long as they want, and let them end the conversation Try to end on next steps, so they know you’re motivated to help them find a good fit elsewhere and be their advocate. Remember, it’s all about them.

The conversation will likely be a blur to them — survival instincts kick in and make it hard to remember how any of it happened — so it’s critical for all the logistics to be written on paper as well. Make sure you or your People Ops person is available to communicate after the fact.

Finally, we always attempt to schedule an exit interview at a separate date and time. It’s an opportunity for the person to speak with someone from People Ops, provide feedback, and maybe even vent a bit. We get value out of the conversation, but again, it’s also about making sure they walk away with closure.

Coordinate login removals

Make someone else on the team responsible for removing the person’s logins and company access during your meeting. By the time the call is over, access is shut off. Have the person’s email forwarded to you or someone else on the team for a while so nothing slips through the cracks.

In some cases, we leave Slack access on for a short time so the person can say goodbye to teammates.

Have a plan for informing the team

In most cases, it’s a good idea to inform the person’s immediate team members before the termination meeting so they’re not surprised.

When it’s called for, we pull the person’s larger team together in a Google Hangout so everyone knows right away.

We also share an announcement in Slack with the whole company to provide context, thank the person for their contributions, let team members know how to get in touch with them should they wish to reach out, and talk about next steps.

All of that is drafted before the fact, and it’s published as soon as the conversation is over.

It’s no fun to be good at firing

It’s sad that firing people is a skill I’ve acquired. Four out of five times I’ve had to fire someone, it was due to a bad hire — and that’s on me. It’s my fault for making the wrong decision, failing to set the person up for success, or failing to set clear expectations.

At the very least, as I’ve learned more about how to hire the right folks, I’ve made fewer and fewer mistakes. I’m proud of the wonderful team we’re building at Help Scout, and I’m thankful that this isn’t a skill I need to use much anymore.

If you’re in the unfortunate position of needing to fire a team member, remember that this is a day the person on the other side of the table (or computer screen) will likely never forget. It’s critically important that when they look back and reflect on the experience, they find that you conducted yourself with compassion, empathy, and an authentic desire to see them succeed elsewhere.

The truth about remote management

I’ve been leading remote teams for a long time now, and if there’s one thing that I know for certain, it’s that it's harder to lead remotely. However, I would never go back to a co-located setup. Even though it’s harder, I’m still passionate about remote work and leadership.

Why? There are two big reasons.

First, running a remote company means you have greater access to talent. Working with people who are at the top of their field, who challenge me, and who bring diverse experiences and perspectives to the table is one of the greatest joys in my life.

Second, it’s easier for creative people to do their best work in a remote environment. It’s a combination of focus, flexibility, and setting that facilitates higher-quality output.

Being a fully remote company is part of Help Scout’s DNA, and I’m confident that our culture, our team, and our product are all better for it.

The truth about remote management is that it’s hard, but it’s unquestionably worth the challenge.